Will Nike break its $1 billion contract with the footballer or have commercial calculations shown that the consumer pool is diverse enough so that for every person that boycotts the brand in protest, there will be another who feels differently about the situation? Shufen Goh of R3 takes a look

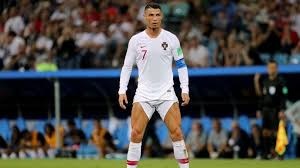

Nike has said it is “deeply concerned by the disturbing allegations” of rape facing footballer Cristiano Ronaldo, one of the few elite athletes with a lifetime contract with the sportswear brand.

The phrase “deeply concerned” is gauged as not being a good enough response for some. Maybe they were hoping for something like ‘abhorrent, repugnant and inconsistent with our values’ – and an instant cutting of the cord as American television network ABC did in response to Roseanne Barr’s racist Twitter rant earlier this year.

But one imagines that Nike, along with many other brands connected to Ronaldo, is taking a wait-and-see approach as the investigation continues. This is just one example of the many value-based decisions brands are facing as movements addressing race, gender and sexuality become more outspoken and legitimised.

These decisions are ‘value-based’ not only because they are about dollars, but because they ask deep questions about marketing and moral responsibility. With the rise of consumer demand for transparency and authenticity, brands who use ambassadors and causes for their ‘purpose-led’ marketing should be prepared for such interrogation.

Who should pay the price for a spokesperson’s bad behaviour? And if a brand is forced to make a moral decision when under the spotlight, is that decision based on actual values or a delayed commercialised response? These might have been occasional topics of debate during an advertiser’s long lunch in the past. However, they are definitely headliner topics demanding an immediate answer nowadays.

Ronaldo is one of the greatest players in football history. So is Lionel Messi, who was convicted of tax fraud in 2017. Rape is not to be on the same spectrum as white-collar crime, but you only need to go through the list of some of the world’s best athletes to come up with a rap sheet that would immediately make the gold sheen vanish from their trophies.

These people are not only objectified by the number of goods that use their name and face, but they are glorified as heroes in our culture. And, in some sense, deservingly so for their sporting achievements.

The truth is that sports brands do not choose ambassadors for their moral superiority; they are chosen for sporting excellence. The criteria for winning the Ballon d’Or is not pureness of heart. There is no category for honesty or kindness at the ESPY Awards. You are awarded for courage and perseverance but not your moral compass.

There are sports that have active players known for domestic abuse and battery, and yet they take to the field week after week. Team owners choose who they want to retain because this has a direct correlation to winning. What a person does off the court is secondary as long as it doesn’t interfere with the game. In some sense, marketing has not been dissimilar.

Our industry champions the intimacy of advertising as an effective way to get close to the consumer, but the unfortunate consequence is this closeness camouflages the true intent of brands in a grey and murky area. At some point, brands stopped being brands and started being friends.

People forgot the basic premise that brands want access to fans (and who has more passionate fans than the great athletes that inspire on the field?) and started seeing brands as extensions of themselves. I [brand], therefore I am, used to be the Holy Grail of marketing. Now though, a reckoning is coming.

Ronaldo’s case has marketers watching Nike’s next move with interest, not only because it puts a stake in the ground about what is able to be ignored and what is not, but because there’s an actual commercial price on moral judgement. Will Nike break its $1 billion contract with the footballer? Or have commercial calculations shown that the consumer pool is diverse enough so that for every person that boycotts the brand in protest, there will be another who feels differently about the situation?

There are people who might feel Nike’s final decision is unfair or distasteful, although not bad enough for them to turn their backs and walk away. Signing a sportsperson as an ambassador does not give brands ownership of athletes. A sponsorship is a contractual agreement that outlines standards and commitments.

However, in the end brands do not have responsibility of their assets because they don’t have control of individuals. The only choice in a moral conversation involving marketing is what stance a brand will choose on an issue and whether consumers want to support that with their wallets.

Nike is not unfamiliar to moral boycotts. It has a history of making calls on social issues. Some have been in its favour and some haven’t. Take its recent choice of Colin Kaepernick as the face of the 30th anniversary of its slogan ‘Just do It’.

People destroyed Nike products in acts of moral outrage and in the name of loyalty to the flag, while others mocked these demonstrations as ‘performative social media outrage’. The contentious ad features a close up of Kaepernick’s face with the words: “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrifice everything.”

We’ll have to see if Nike decides to take advice from one of its own.

Shufen Goh is a principal at R3, a global consultancy firm