Companies from Unilever to Tiffany flock to ‘key opinion leaders’ to reach consumers

Gogoboi spent a month wearing outfits matching Pokémon characters. Yao Chen — China’s answer to Angelina Jolie — hangs out with refugees. Papi Jiang swears way too much.

Meet China’s key opinion leaders (KOLs). Like America’s YouTube stars, they are a diverse bunch who range from the girl next door to renowned actors. They boast millions of followers — 80m in actress Yao Chen’s case — and some have, like their US peers, come badly unstuck. But in one respect they have trumped the celebrities of the west: monetising their lives.

“More than any other country, [KOLs] have taken the lead to be a true media vehicle,” says Greg Paull, principal of R3, a global marketing consultancy. “Much like you would use a TV campaign or other promotion, most marketers in China have a KOL strategy.”

Makers of everything from shampoo and chocolate such as Unilever, to purveyors of designer handbags including Burberry and Gucci, have swarmed to these influencers as a way to advertise their goods.

That has resulted in some unusual bedfellows. Watchmaker Jaeger-LeCoultre saw its brand awareness, as measured by the Baidu Index, more than double, after running a campaign with girl-next-door vlogger Papi Jiang. Actor Kris Wu has boosted sales for designers Bulgari and Burberry.

The two are among the teen idols being enlisted by luxury brands such as Longine sand Tiffany to woo younger shoppers.

As multinationals latch on to KOLs as a means of selling goods to aspirational Chinese consumers, the paychecks they command are rising, according to ad agencies. Jaeger-LeCoultre paid “at least” Rmb5m ($731,000) for Ms Jiang’s 30-second video, estimates Kevin Gentle of Madjor, a digital branding agency.

But the results also can be big. Actress Yang Mi shared her birthday party, thrown by designer Michael Kors in a New York hotel, with her 72m followers on microblogging and livestreaming site Weibo — generating more than 12m comments and likes, according to digital agency L2.

Hitting the big time

In a uniquely Chinese twist, an entire industry profiting fromthe KOLs’ ascent has sprung up. While YouTubers in the west are also paid to munch Oreo cookies on video or wear a designer’s clothes, KOLs in China also pull in their own funds directly.

On top of advertising dollars, they make money from fans who can send virtual giftsand cash online, as well as paid endorsements and sponsorships — such as jeweller DeBeers, which sponsored the wedding of celeb couple Liu Shishi and Wu Qilong.

At the top of the ladder, some KOLs even become investment vehicles in themselves: Ms Jiang, before China’s regulators took issue with her swearing, raised just shy of $2m from venture capital investment into her company. SNH48, a funky girl band as well known for engaging with fans online as for their fishnet tights and distressed shorts, helped secure a $150m investment for their media group, Star48 Culture and Media Group, last month.

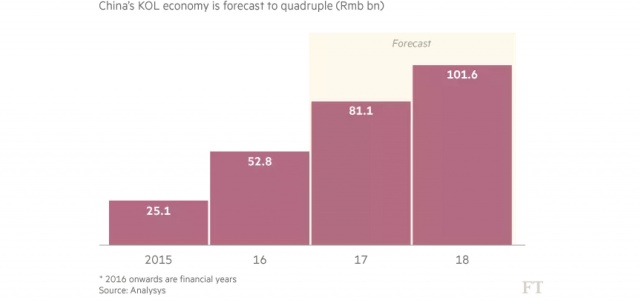

The KOL economy was estimated at Rmb58bn by CBNData in 2015 — equivalent to more than that year’s gross box-office receipts. Consultancy Analysis projects revenues will reach Rmb100bn next year.

Microbloggers on Weibo — which has overtaken US peer Twitter, which is blocked in China, in terms of both market capitalisation and subscriber numbers — had pulled in $1.7bn by October last year, according to Xinhua.

The KOLs owe their rise to the flourishing livestreaming industry, much as YouTube buoyed its screen celebrities. But a shift to short-form videos has breathed new life into the industry — especially for advertisers who produce their own content, such as behind-the-scenes footage of fashion shows.

Like YouTube, China’s tech trinity of Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent all have video streaming platforms. But it is those targeting shorter-form video, such as Weibo, dating app and livestreaming player Momo, and social platform YY, that are attracting the most attention from advertisers.

Livestreaming periodically falls foul of the regulators — as highlighted by Beijing’s recent crackdown on inappropriate content. Last week, new rules prompted technology and media companies such as Sina Weibo and Tencent to close down 291 videostreaming platforms and fire almost 10,000 journalists.

But the industry has been growing fast. There are more than 200 livestreaming apps, according to market research consultancy Frost & Sullivan, with over 200m registered users.

When it comes to livestreaming “a lot of platforms have a greater level of interactivity between the KOL and the watcher”, says Brian Buchwald, cofounder and chief executive of consumer research company Bomoda. “They encourage live engagement . . . with the KOLs.”

Viewers, however, tend to be platform-neutral, says Joe Ngai, managing partner of McKinsey’s Greater China practice: “They follow the person, not the platform.”

“We have clients who move all of their advertising online and KOL endorsement is the primary driver outside of Baidu search,” says Mr Buchwald. “They are trying to put as much money into KOLs as they can.”

Souce: Financial Times