Asia is the largest e-commerce region in the world, turning over $877.61 billion in transactions in 2015, and India’s contribution was a staggering 129% increase in sales[1]. This growth is expected to increase at an exponential rate on the back of an exploding internet population and an increase in online shoppers. Three-year growth rankings for India outperform China, the US and the global average at 68%. Morgan Stanley has adjusted the projected size of the e-commerce market in India in 2020 to $119 billion, up from $102 billion[2].

I experienced this phenomenon firsthand when I was in India last week. My friend’s father complained to me that he hated spending time at his daughter’s house – despite his two adorable granddaughters – because all he did all day was open the door to receive packages from Amazon, Flipkart, Jabong, Myntra, Snapdeal and several others. Another young mother lamented how she deleted online shopping apps from her phone every few months so she could do an ‘online shopping detox.’

With a population of 1.3 billion, 350 million internet users and approximately 39 million people making online purchases[3], India’s online shopping population is growing. Let’s take a closer look at the 4 Cs of this complex business in an overtly fragmented market.

1. Competition: Who are the Major E-commerce Players?

Local e-commerce startups like Flipkart and Snapdeal are valued at several billion dollars each by investors, and venture capitalists are constantly on the lookout for the next big thing. Mergers and acquisitions are the order of the day. There is intense competition between these two India e-commerce giants, who have both acquired a series of start-ups to help them achieve their individual business goals. Snapdeal acquired Freecharge (an online recharge platform) for an estimated $400 million, while Flipkart bought Myntra, a large fashion e-commerce site with an impressive inventory.

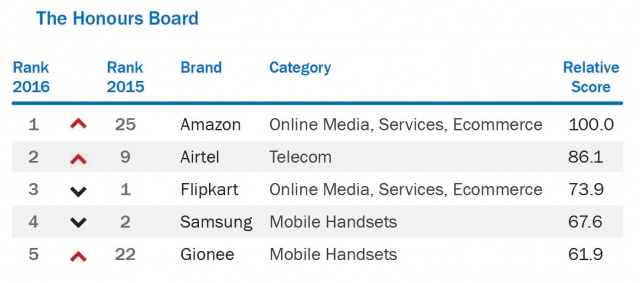

While global player Amazon arrived late to the e-commerce party, it is already making waves. Amazon recently dethroned Flipkart on afaqs!’s 11th Buzziest Brands of India list.

2. Cash: Can India Shift to Mobile Payments?

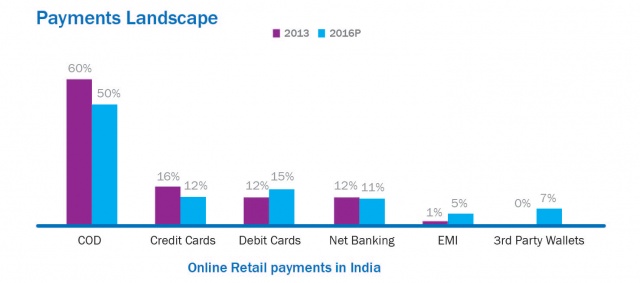

Cash is king in India and still accounts for nearly 60% of payments for online purchases.[4] Delivery is outsourced to courier companies who collect and hold the cash for several weeks, while the e-commerce company has to restock inventory it can receive the payment. Dealing with cash is a manual process with several associated risks, but credit and debit card penetration is low and many consumers still have reservations about putting their payment information online.

However, there has been a significant rise in digital wallets with payment platform, Paytm. The platform is estimated to reach four million merchants by the end of 2016, making it the largest mobile wallet option. Creating a digital ecosystem of its own is Snapdeal. With three times as many sellers as Flipkart, Snapdeal is trying to close the loop on payments and directly compete with Paytm. It acquired FreeCharge, a recharge and utility payments platform, in order to launch FreeCharge Digital Wallet, which enables users to have a single account and wallet for transacting on both Snapdeal and FreeCharge.

Amazon has also applied for an e-wallet license under Amazon Online Distribution Services (AODS), which offers payments, logistics and services, allowing merchants to sell through their own websites using Pay With Amazon.

3. Connectivity: Mobile Commerce is on the Rise

India’s market for mobile commerce was worth $2 billion in 2014 and is estimated to grow to $19 billion by 2019[5]. The nation sees an average of 17 app downloads per user, four of which are paid[6]. Leading e-commerce player, Snapdeal, has a mobile-only strategy, and has seen over 75% of its traffic coming from mobile. There are a few other e-commerce firms in India that are on the app-only track, such as Ola (transportation), Faasos (food), TinyOwl (food ordering) and Grofers (home delivery of groceries and other items). Securing prime real estate on mobile users’ home screen is critical – this is where the war for the consumer will be fought.

After its debut in 2014, Flipkart’s The Big Million Days sale 2015 was limited to its smartphone app. However, not everyone has achieved success with the mobile-only model. Myntra tried, but brought back its mobile site as consumers wanted the choice of device they were familiar with, such as computers and tablets, and not just mobile. Even though Amazon India currently gets 70% of its traffic from mobile[7], it is also not a proponent of the mobile-only model.

4. Creativity: More than Just Transactions

In this highly competitive and regulated sector, players are trying to inject creativity into their offerings Flipkart-Myntra recently launched a fashion incubator for up-and-coming entrepreneurs in the fashion field. Increased partnerships between Indian fashion e-commerce sites and international fashion brands are also popular, like Jabong’s deal with a London-based high street brand River Island, and Myntra’s contract with a Dutch youth fashion brand called Scotch & Soda.

In a bid to increase customer satisfaction, online fashion retailers are aiming to introduce other services like altering & fitting clothes and customized tailoring. Amazon has a travelling studio on wheels, offering training and photography services to help show owners come online.

This also shows how success in the e-commerce space is never a solo effort. In order to succeed, marketing, sales and distribution teams need to work hand-in-hand within the organization. Externally, having the right ecosystem of agency partnerships is a critical success factor. In R3’s experience, having a collaborative agency support model ensures brands stay focus on the customer, and harness the creativity of its partners to push boundaries.

So what’s holding India back from becoming in the next China of e-commerce?

Besides taxation and regulatory policies (which need a separate article dedicated to them), the two key aspects that are hampering growth are the logistics and sustainability of the business model. Last mile delivery is an area of concern with no immediate solution in sight due to the poor infrastructure in the country. Third-party carriers are used for shipping and there is no one

national player. Each region/city uses its own network of local couriers, many of whom still use bicycles to make the final delivery.

Another big issue, competitive pricing and discounts, has become more pressing as only last week new government rules regulating e-commerce marketplaces were put into place. Department of Industrial Promotion and Policy (DIPP) guidelines state that “E-commerce entities providing marketplace will not directly or indirectly influence the sale price of goods or services and shall maintain a level playing field.”

Furthermore, Indian consumers have low brand loyalty, which is driven in part by discounts. Studies [8] reveal that 54% of customers will switch brands if given more benefits by another brand, and 62% customers believe that monetary benefits (cash back, discounts, and rewards) are the most important aspect of a loyalty program.

So what does this mean for the current discount drive that all players are on? Most sites finance the seller’s discounts with their investor funding. With the new regulations in place and once VC funds start to dry out, prices may not be as lucrative. Will consumers still shop online? Or will they flock back to malls, local boutiques and kinara (corner stores)?

That’s the billion-dollar question – Are Indian consumers so hooked on online shopping that they won’t go back to brick-and-mortar stores even after the discounts die?

Seema Punwani is a Principal Consultant with R3.

[1] eMarketer, Dec 2015

[2] Morgan Stanley Research Report, 2016

[3] Tech in Asia Data, Oct 2015

[4] RBI Website and Accel Reports

[5] Zinnov report, April 2015

[6] Vserv report, India’s love affairs with mobile apps, Sept 2015

[7] Comscore, Dec 2015

[8] eMart Solutions: How Loyal are Indian Consumers – India Consumer Loyalty Study 2015